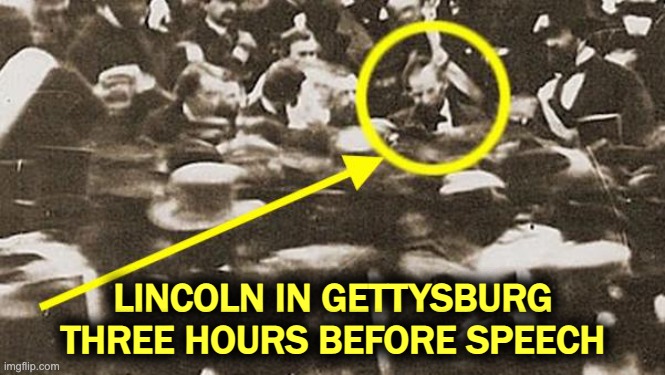

The Battle of Gettysburg, one of the most noted battles of the Civil War, was fought on July 1–3, 1863. On November 19, 1863, President Lincoln dedicated the field as a national cemetery. He delivered a two-minute speech that was to become immortal, the Gettysburg Address (the picture above is one of only two images of Lincoln at Gettysburg. The yellow arrow points him out).

The Battle of Gettysburg, fought four months earlier, was the bloodiest battle of the very bloody Civil War. Over three days, more than 45,000 men were killed, injured, captured, or missing. The battle also proved to be the turning point of the war. The South’s defeat and retreat from Gettysburg marked the last Confederate invasion of Northern territory and the beginning of the Army of the South’s ultimate decline.

President Lincoln wasn’t even the main attraction on that day in Pennsylvania 159 years ago. Edward Everett, one of the most famous orators of the day, was the keynote speaker. But in Lincoln’s speech (which was not written on the back of an envelope) of a mere 278 words, the 16th President not only dedicated a national cemetery but rededicated America to the hopes and dreams expressed in the Declaration of Independence.

At the time of its delivery, the speech was relegated to the inside pages of the papers, while the two-hour address by Edward Everett caught the headlines more for its length than its content.

The NY Times reported at the time:

President LINCOLN’s brief address was delivered in a clear, loud tone of voice, which could be distinctly heard at the extreme limits of the large assemblage. It was delivered (or rather read from a sheet of paper which the speaker held in his hand) in a very deliberate manner, with strong emphasis, and with a most business-like air.

Other papers trashed the speech

The Patriot and Union of nearby Harrisburg wrote:

“The President acted without sense and without constraint in a panorama that was gotten up more for the benefit of his party than for the honor of the deed….We pass over the silly remarks of the President; for the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of.”

In 2013, 150 years after Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address, The Harrisburg Patriot and Union wrote an editorial retracting its original trashing of Lincoln’s speech. The retraction began, “Seven score and ten years ago, the forefathers of this media institution brought forth to its audience a judgment so flawed, so tainted by hubris, so lacking in the perspective history would bring, that it cannot remain unaddressed in our archives.”

The Chicago Times put it this way,

“The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat and dish-watery utterances of the man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States.”

That negative review may have resulted from the Chicago Times’ liberal slant and the fact that Abraham Lincoln was America’s first Republican President.

Modern politicians should take note the address is concise. Also, there are no sob stories about an obscure person Lincoln once met as politicians do today, and nowhere in the address are the words; me, my, or I. This speech was about a vision of the future of America, not Lincoln, yet 159 years later, it is remembered better than speeches modern politicians made 159 hours ago.

Read the full speech below. It is a masterpiece:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

There are five “original copies” of the Gettysburg Address, and each is slightly different in wording and punctuation. The version below is displayed in the Lincoln Room of the White House.