Controversy has arisen over the Israeli government’s recent decision to temporarily prevent non-Israelis from entering the country because of the ongoing Covid-19 crisis. exaggerating the diaspora’s distress

American businessman Martin Oliner (writing in the Jerusalem Post on January 1) recalled that Theodor Herzl cited the “distress of the Jews” in explaining the need for a Jewish state in his 1896 book, Der Judenstaat. Today, according to Oliner, “Jews around the world are once again in distress,” this time because of the Israeli travel decision.

Unfortunately, many Diaspora Jews are temporarily unable to attend family events in Israel or complete business deals with their Israeli partners. But when one surveys the suffering that Jews were enduring in the 1890s, when Herzl was writing his book. Is there really a basis for comparing it to the distress that some contemporary Diaspora Jews are experiencing?

In Czarist Russia, discrimination and violence against Jews reached such levels that U.S. President Benjamin Harrison, in his annual message to Congress in 1891, denounced “the severe and oppressive civil restrictions… [and other] harsh measures now being enforced against the Hebrews in Russia,” as a result of which, he forecast, “over 1,000,000 [Jews] will be forced from Russia within a few years.” Konstantin Pobedonostsev, adviser to the Czar, reportedly remarked in 1894 that one-third of Russian Jews should leave the country, one-third should become Christians, and one-third should die.

In The Russian Jew Under Tsars and Soviets, the eminent historian Salo Baron found that after the ascension to power of Czar Nicholas II in 1894, “the old screws of legal and administrative discrimination [against Jews] were turned more tightly.” The quota on Jews admitted to Russian universities and colleges was lowered from 7 percent to 3 percent, and the number of Jewish paupers in Russia grew by 27 percent from 1894 to 1898. “In many communities, fully 50 percent of the Jewish population depended on charity,” Baron wrote. Discriminatory legislation (the infamous May Laws) was partially extended to Russian-occupied Poland in 1891, deepening the misery of Polish Jewry.

In Germany, there was a massive surge of Antisemitism in the 1890s, ranging from a blood libel trial in 1891-1892 to a series of electoral victories for Jew-haters. The number of openly anti-semitic deputies in the Reichstag increased from one to five in 1890 and to sixteen in 1893. The Conservative Party became the first major political party in modern Germany to embrace Antisemitism, vowing to “fight the multifarious and obtrusive Jewish influence that decomposes our people’s life.”

The rising tide of Antisemitism prompted German Jews to create defense groups such as the Association for Defense Against Antisemitism (1890) and the Association for Defense Against Antisemitism (1892), as well as the more assimilationist Centralverein of German Citizens of Jewish Faith (1893), and, because of campus antisemitism, the Confederation of Jewish Fraternities (1896).

Herzl was particularly troubled by events in France and Austria, where he had lived since his teens. The Dreyfus Affair, which Herzl followed closely, began in 1894, culminating in mass anti-Jewish riots in Paris in 1898. In Austria, the openly anti-semitic Karl Lueger became mayor of Vienna in 1895 and was repeatedly re-elected. Adolf Hitler later cited Lueger as a source of inspiration.

This snapshot of the distress suffered by some major Diaspora communities in the 1890s is obviously quite different from what Jews in the Five Towns or Beverly Hills are experiencing today.

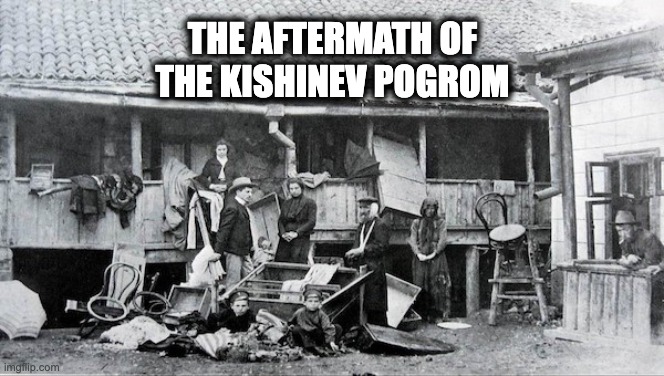

[ Beginning on Easter Sunday, April 6, 1903, “the Jewish community of Kishinev in czarist Russia suffered two days of mob violence that shocked the world and changed the course of Jewish history.” Provoked by a medieval blood libel, flashed around the globe by modern communications, Kishinev was the last Pogrom of the Middle Ages and the first atrocity of the 20th century.” The event evoked a worldwide wave of Jewish outrage that laid the foundations of modern Israel, gave birth to contemporary American-Jewish activism, and helped bring about the downfall of the czarist regime.

Because of that Pogrom, the great Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky became an activist for the Zionist cause—allowing the Jews to return to and be allowed to create a state on the land they were thrown out of two thousand years earlier].

This is not to minimize the unhappiness of those who have missed family celebrations or whose academic conferences have had to be conducted via Zoom. But the history of the Jewish people is filled with all too many instances of life-or-death distress. Careless historical comparisons contribute little to the public conversation concerning temporary travel restrictions to Israel.

Dr. Medoff is director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies in Washington, D.C. www.WymanInstitute.org and the author of many books about the Holocaust.] He is a “no holds barred” truth-teller.