On March 26, 1979, the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt was signed in Washington, D.C. But the peace treaty almost never happened because U.S. President Jimmy Carter tried to scuttle the talks at their origin— when Anwar Sadat said he would visit Jerusalem. But Sadat went anyway and arrived at the Israeli Capital 40-Years-Ago today, November 19, 1977.

Carter was pushing a “Geneva Peace Process” which included all of the Arab Nations, but Sadat felt that the process was all “show” and couldn’t see a way to form a united negotiating bloc with his Arab (mainly Syria, Libya, and Iraq) allies.

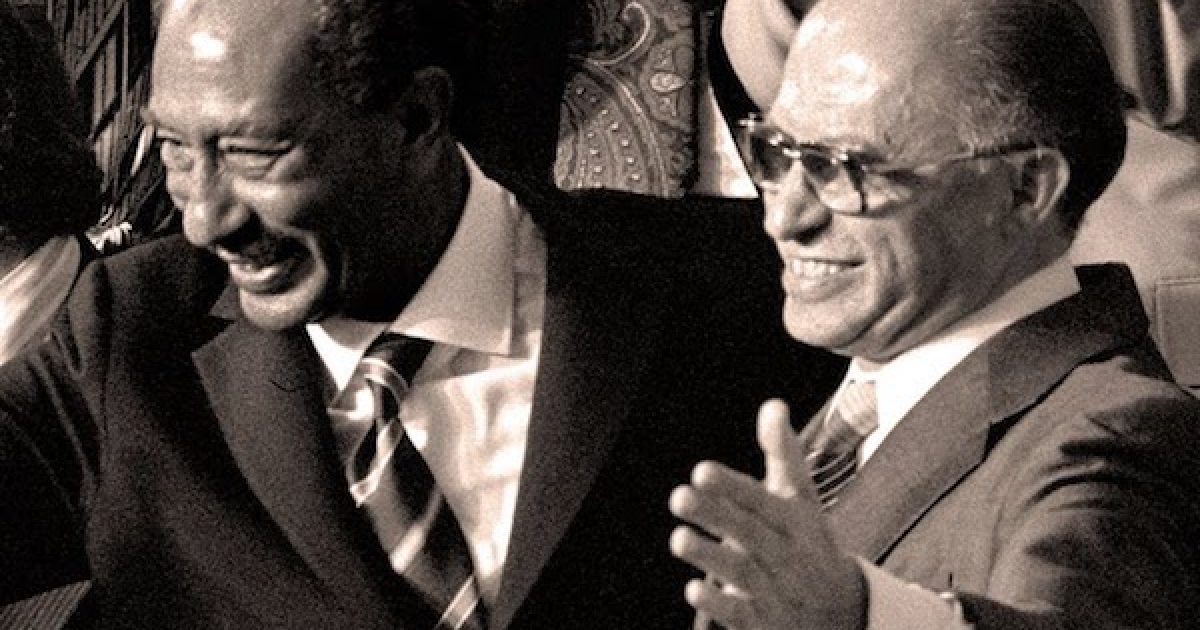

So Sadat took the initiative and on November 9, 1977, he delivered a speech in Egypt that stunned the world. He stated that he would travel anywhere, “even Jerusalem,” to discuss peace.

That speech led Begin government to declare that, if Israel thought that Sadat would accept an invitation, Israel would invite him. Actually, it Walter Cronkite negotiated the entire thing.

Prime Minister Begin’s response to Sadat’s initiative, demonstrated a willingness to engage the Egyptian leader. Like Sadat, Begin also saw many reasons why bilateral talks would be in his country’s best interests. It would afford Israel the opportunity to negotiate only with Egypt instead of with a larger Arab delegation that might try to use its size to make unwelcome or unacceptable demands.

Thus the two began bilateral talks. According to Yossi Alpher, a former senior adviser to Prime Minister Ehud Barak and former director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University:

Carter wanted his Geneva talks. He didn’t care that the peace process already begun by Sadat and Begin might lead to peace, Carter wanted his plan or nothing. You see Carter’s vision of a Geneva conference would be run by the U.S. and the USSR, and Israel would be facing the terrorist PLO, and Israel’s neighbors including, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Lebanon, and Jordan. It would not be a negotiation because when one considers that the Arab countries were Soviet satellites, and the Carter administration’s ideological orientation was anti-Israel it seemed to ensure the conference would be all the participants vs. the Jewish State.

Thankfully Carter couldn’t stop the approaching peace train. Within days Israeli journalists were allowed into Cairo, breaking a symbolic barrier, and from there the peace process quickly gained momentum.

So you see Carter did his very best to screw up what became his only foreign policy success (unless you want to count the release of the hostages from the Iranian embassy, but that would have never happened if Ronald Reagan wasn’t about to be inaugurated as President)

=