Records responsive to a FOIA request were posted by the Department of Justice this week, and they show that 14 members of Robert Mueller’s special counsel team “wiped” data from their government-issued smartphones after the DOJ inspector general requested the phones from them for review. wiped by Mueller team

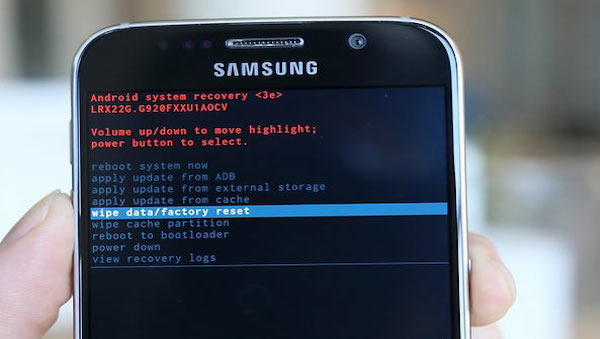

The special counsel geniuses used several methods, including entering the wrong passcode 10 times to automatically trigger a data wipe. Some individuals set phones in airplane mode with incorrect passwords or no passwords provided, making the data inaccessible when the phone was turned over.

The latter situation might prompt a law enforcement request to the phone vendor to unlock the data. Although this wasn’t a criminal proceeding – but rather an IG investigation – the data at issue constitute something the agency is entitled to recover. It’s a set of federal records, and the agency is the contract customer.

But since it wasn’t a criminal proceeding, obstruction of justice doesn’t come into play. The behavior in question is obvious and deplorable, but unless the individuals are referred for charges in some related way, going after them in court for wiping data from their phones isn’t an option. (In any case, you’d have to prove they did it deliberately, to make records destruction the criminal charge).

Notably, however, Andrew Weissmann, Mueller’s longtime lieutenant and “pit bull,” was one of the 14 wipers.

So was Brandon Van Grack, one of the prosecutors on the Michael Flynn case, whose compliance with Brady records disclosure was “called into question” separately by DOJ records unsealed in late April 2020.

The scope of responsibilities for both Weissmann and Van Grack, and probably some others on the Mueller team, could ultimately facilitate charges and conviction if wiping their phone data can be credibly linked to misconduct in the Mueller-directed criminal cases.

Andrew Weissmann. LAT/CSPAN video, YouTube

But the question is whether that link could, in fact, be established. Prosecutors would need a view of the data wiped from those phones.

The members of the special counsel team evidently had that in mind in their mass wiping operation. As Sundance observes at Conservative Treehouse, “Wiping your phone to hide damaging information only works if the other phone you are communicating with wipes the same data. Guess what happened? Yup, exactly that.” (Sundance also has an excellent graphic depicting all 14 of the Ingenious Wipers, which you should go take a look at.)

So, wiped from both ends. Thorough.

But we’ve actually been close to here before, back when the text message records of Peter Strzok and Lisa Page had miraculously-timed missing data periods, discovered after they left the special counsel team in the summer of 2017. And we learned from the IG report on the recovery of their smartphone data that the FBI uses a collection tool to harvest text messages sent from and to agency-issued phones.

The FBI does that because text messages (and other informal, direct electronic messages) are now considered federal records, in accordance with the Federal Records Accountability Act of 2014. As a DOJ agency, the FBI is subject to DOJ electronic records guidance updated in accordance with the 2014 Act, cited in the IG report as DOJ Policy Statement 0801.04, approved September 21, 2016 (see p. 5). (As regards the special counsel per se, it isn’t clear from the IG report what the DOJ is doing about collecting text messages and other smartphone records for retention. The National Archives put out a bulletin on managing electronic messages as federal records in 2015, with in-house data collection as a featured option for retaining federal records from smartphones.)

We can note that the updated DOJ guidance, based on the 2014 federal records law, had barely been approved by the time the Strzok/Page texts from late 2016 and early 2017 went missing. It had been in place longer when the Mueller team was trading texts in 2017 and early 2018.

The IG report on the Strzok/Page texts doesn’t give the name of the vendor with which the FBI contracts the collection tool. Still, it’s apparently a third party separate from the phone manufacturer and the telecom service provider (in the Strzok and Page case, Samsung and Verizon, respectively).

A complete IT systems search turned up separate caches of the Strzok and Page text messages. DOJ also worked with the Department of Defense to recover information from the phones and had some success doing that as well. As IT-savvy commenters at various websites and on social media have pointed out, wiping the data on the phones, using the methods described, doesn’t actually eliminate it entirely. It typically removes the data pointers in the “header” that make the 1s and 0s display as an organized file event. The actual data held in memory may thus be disorganized, but can usually be recovered by specialists. (This is why Hillary had her phone attacked with Bleach Bit – a program, not actual bleach – and a hammer.)

Keep in mind, DOJ knew about this data wipeage by special counsel team members two and a half years ago. We’re just finding out, but DOJ isn’t. They’ve known since the IG discovered it happened – with a relevant data timeframe of June 2017 to early 2018.

So it’s possible they were able to recover much of the wiped data by the same means they recovered Strzok’s and Page’s texts.

There’s also a middle between the two phone ends that got wiped. The telecom service providers have records of data transactions, and some of them retain the records for a considerable period. The IG found out in the Strzok/Page case that Verizon didn’t; the company was only keeping the text records for 5-7 days.

And as the IG report noted, “Their retention period is the same whether the customer is the government or a private citizen. Accordingly, Verizon was not able to produce any text messages for the FBI issued mobile devices in question.” (p. 10)

But note this as well: the IG was entitled to request such records from Verizon because the data transactions are federal records. No warrant of any kind is necessary. It’s not something subject to FISA or Patriot Act justifications. Government-issued smartphones are inherently subject to federal monitoring and record retention requirements. The federal agency is the party contracting with the service provider, not the employee, and the employee has no privacy expectations on government-issued electronic devices.

The IG report on the Strzok/Page texts, dated December 2018, makes it pretty clear the DOJ/FBI effort to manage smartphone transaction data as federal records is a work in progress. Indeed it was at that time.

But note that the DOJ hierarchy became aware of the records retention issue between late 2017 and December of 2018, the date of the report. That was the same period in which the IG discovered the data wipeage on the other 14 Mueller team members’ phones.

So we have reason to hope that much of their data could still be recovered, in spite of their best efforts. (It seems unlikely, moreover, that no action was taken to improve or modernize the department’s ability to retain and access such vital federal records until later than that. We also have reason to hope that someone in DOJ has seen the wisdom of contracting with the telecom service providers for longer retention of data transactions involving government-contracted phones. There should be no reason why that can’t be done.)

Interrogating the DOJ hierarchy about its response to the epidemic of missing phone data from the special counsel is also clearly in order. Whatever wringer John Durham hasn’t put the relevant personalities through by now, Congress certainly should.

The bottom line from this whole episode may be more advantageous than we might think. At this point, responsible federal officials could have both the record of an attempted cover-up and much of the information covered up. That would mean they’d have the special counsel team, red-handed.

We don’t know how long it would have taken to achieve that data recovery. It apparently took the DOJ months to recover the missing Strzok/Page texts. But to the extent possible, it was probably accomplished in the case of the other special counsel team members by the time Durham launched his investigation (in early 2019).

It’s interesting to me that this has come out just now. Maybe it’s because it’s time for the public to know about it. That could be for more than one reason; keep in mind that this is only one of dozens of complex forensic threads Durham’s team has had to pull. I advise against despair. Let’s see where this goes.

Meanwhile, Sundance posted a video showing the level of effort it takes to wipe data using the 10-wrong-passcode-entry method. It’s not something anyone could do unwittingly.

Crossposted with Liberty Unyielding

wiped by Mueller team , wiped by Mueller team , wiped by Mueller team, wiped by Mueller team

https;//lidblog1.wpenginepowered.com