By Sandra Kessler, Herut Member

Israel is in the midst of what may be its gravest crisis since the 1948 War for Independence. Israel’s imperative is nothing less than the complete destruction of Hamas, the criminal gang of terrorists that has ruled Gaza for 16 years in absolute tyranny. As Hamas has itself announced loud and clear to whoever will listen, Palestinians glorify death, while the Jews love life. Under Hamas and other Palestinian Terrorist leaders, children are taught from the cradle to hate Jews, to learn how to murder Jews, and to aspire to martyrdom as their highest calling.

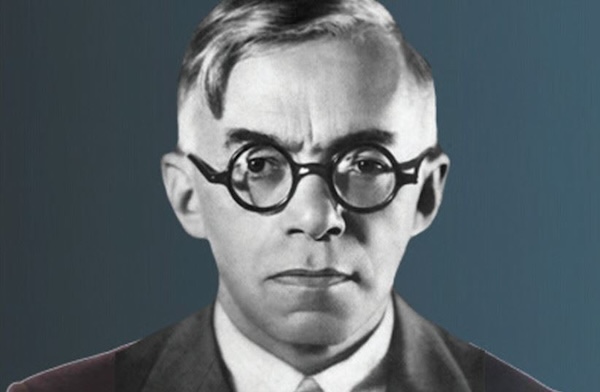

Those of us who support Israel unapologetically are praying for victory, once and for all, over this Death Cult. Once achieved, Israel will undoubtedly help rebuild the Palestinian areas if they guarantee peace and cooperation. As a Jew of the Diaspora and an Unapologetic Zionist, I hope Israel turns for inspiration and guidance to the wisdom of the late Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism, whose 143rd birthday falls on October 17th.

Ze’ev Jabotinsky was born in 1880 in Odessa, at that time, a sophisticated, multicultural urban center of Czarist Russia. Ze’ev was only 6 when his father died, leaving his family in reduced circumstances. Despite this, Ze’ev’s precocious intellect enabled him to pursue the kind of education not available to most Jews in Czarist Russia. His educational journey led him to leave Russia as a teenager to immerse himself in cosmopolitan Italy’s intellectual and artistic riches and then to Bern, Switzerland, where he earned his law degree. Although he was in Bern at the time of the first Zionist Congress in 1896, he was not yet fully engaged in the effort to return Jews to their ancient homeland.

It was the Kishinev Pogrom of 1903, the deadliest and most destructive of the numerous attacks on Jews during Czarist rule that was the defining moment for Jabotinsky in his journey to become one of the most important and honored of Zionist leaders. His newspaper sent him there to oversee the distribution of the aid funds he had shamed them into raising to help the pogrom’s victims. What he witnessed and heard from survivors both shocked and dismayed him. Shocked at the level of barbarity they had suffered. But dismayed at the apparent passivity of the victims, who seemed to have become inured to the periodic violence, endured what they could, then cleaned up while hoping for better next time.

In his excellent biography of Jabotinsky, Hillel Halkin says that his experience at Kishinev solidified his belief that Jews should no longer live where they would always be hated.

Jabotinsky now dedicated his life to the Zionist cause. His speeches, writings, and exploits are legendary. Among his accomplishments was the founding of Betar, the grassroots organization, hoping they would someday use these skills in the reborn Jewish National State. Jabotinsky also successfully persuaded the British in WWI to create a Jewish Legion to help the Allies reach victory in the Middle East.

In the aftermath of WWI, Jabotinsky split from the majority stream of Zionism to rethink the principles needed to guide the development of the future Israel, even as the path to Jewish independence was littered with new obstacles despite the Balfour Declaration’s promises.

Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionism differed from previous Zionist ideologies in critical ways. For one thing, he rejected the notion that an economically thriving and secure nation could be built entirely on the socialist ideals of the Labor Zionists.

Jabotinsky’s Revisionist vision included a mixed economy based on capitalist enterprise and a culture that elevated the individual. He believed that Jews, like all peoples, ran the spectrum of human endeavor. From the most exalted scholar and banker to the lowest factory worker and prostitute, these were all Jews and deserved a place in the Jewish nation.

Among his most famous statements is this: “We do not have to apologize for anything. We are a people like all other people; we do not intend to be better than the rest. As one of the first conditions for equality, we demand the right to have our own villains, exactly as other people have them. We do not have to account to anybody, we are not to sit for anybody’s examination, and nobody is old enough to call on us to answer. We came before them and will leave after them. We are what we are, good for ourselves; we will not change or want to.”

Despite his belief in individualism (Every Jew a King), Jabotinsky recognized no society could long endure without citizens who are unified around a shared set of values, principles, and the willingness to defend what they have built.

In his 1923 essay “The Iron Wall,” Jabotinsky presents a powerful image of an impregnable barrier between Israel and its enemies that could only be sustained when a society remains unified around its foundational principles. The Iron Wall is a tangible representation of the strength and determination of the nation’s citizens to never allow cracks to develop that would enable the enemy to infiltrate. He understood the eternal principle that peace can only be sustained through strength. The kind of unified strength that your enemy realizes would be futile to try to break.

Like Moses before him, Jabotinsky never reached the Promised Land. Sadly, he died at the height of his powers in 1940. WWII had already begun. Jabotinsky foresaw what became the Holocaust. That was one of the things that drove him to work so hard to make a reborn Israel a reality. There is a particular irony in that he died on the eve of the Final Solution. But perhaps it is a blessing that he was spared the anguish.

a

|

|

|

a