The problem with Donald Trump’s latest remark about genes and blood is not whether he ever read Mein Kampf or was influenced by Adolf Hitler’s racial theories, as some pundits are speculating. The problem is that he could just as easily have been influenced by Woodrow Wilson or Franklin D. Roosevelt—because, sadly, dumb and dangerous ideas about race have a long history in the United States, even reaching all the way to the White House, under both parties.

The latest controversy concerns Trump’s declaration, at a December 16 campaign event in New Hampshire, that illegal immigrants “are poisoning the blood of our country.” When he was asked in a December 22 radio interview about critics comparing that remark to some of Hitler’s speeches, the former president replied, “I know nothing about Hitler. I’m not a student of Hitler. I never read his works.”

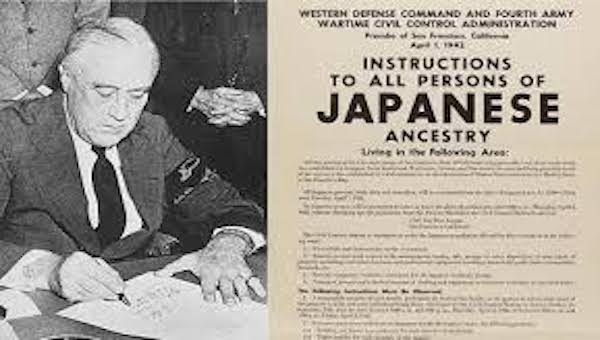

Trump might be surprised to learn what some prominent Americans—including several presidents and future presidents—said about race and immigration a century ago. Especially noteworthy are the writings of Franklin D. Roosevelt on the subject, which were frighteningly similar to what Trump has been saying, including the accusation that immigrants were “poisoning” American society.

“[F]or a good many years to come European immigration should remain greatly restricted,” Roosevelt wrote in 1925, just before he was elected governor of New York. “We have, unfortunately, a great many thousand foreigners who got in here and must be digested. For fifty years, the United States ate a meal altogether too large—much of the food was digestible. Still, some of it was almost poisonous.” He asserted that “the United States must, for a short time at least, stop eating, and when it resumes, should confine itself to the most readily assimilable foodstuffs.”

Many of FDR’s predecessors felt the same way. His distant cousin Theodore Roosevelt wrote in 1897—not long before he became president—that “Anglo-Saxon women” had an obligation to bear children “numerous enough so that the race shall increase and not decrease” and that everything should be done “keep for the white race the best portion of the new world’s surface.”

Woodrow Wilson authored a book in 1902 in which he yearned for the days when “men of the sturdy stocks of the north of Europe had made up the main strain of foreign blood which was every year added to the vital working force of the country.” He was worried that “the countries of the south of Europe were disburdening themselves of the more sordid and hapless elements of their population,” whom he considered racially undesirable.

Wilson railed against “Chinese and Japanese coolie immigration” in his 1912 presidential campaign. “The whole question is one of assimilation of diverse races,” he wrote. We cannot make a homogeneous population out of people who do not blend with the Caucasian race…Oriental coolieism will give us another race problem to solve…”

Wilson, a Democrat, and his successor, Republican Warren Harding, disagreed on many issues, but race was not one of them. There is “a fundamental, eternal, inescapable difference” between the races, President Harding declared in a speech in 1921. “Racial amalgamation there cannot be.”

As vice president under Harding—and soon to become president—Calvin Coolidge wrote in Good Housekeeping magazine in 1921: “There are racial considerations too grave to be brushed aside for any sentimental reasons. Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend. The Nordics propagate themselves successfully. With other races, the outcome shows deterioration on both sides.”

It was precisely such attitudes that brought about the adoption of restrictive U.S. immigration laws based on national origins in the early 1920s. “We have closed the doors just in time to prevent our Nordic population being overrun by the lower races,” Senator David A. Reed, one of the authors of the new legislation, explained in a New York Times op-ed. “The racial composition of America at the present time thus is made permanent.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed. In the 1920s—just before he was elected governor of New York—FDR wrote several articles warning that “the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results.” He preferred that America welcome European immigrants with “blood of the right sort.” In 1939, as president, Roosevelt privately boasted to a Senate ally that “we know there is no Jewish blood in our veins.”

What made Franklin Roosevelt’s sentiments on race and immigration so consequential is that he happened to be president during the period when Jewish refugees were desperately trying to flee from the Nazis. His response to the crisis was to implement a harsh policy of suppressing Jewish refugee immigration far below what the existing laws allowed. Thanks to FDR’s policies, 190,000 quota places from Nazi Germany and Axis-occupied countries were left unused from 1933 to 1945.

Keeping most Jews away from America’s shores was consistent with FDR’s vision of the United States as a country that he hoped would be overwhelmingly white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant. In Roosevelt’s view, even the few Jews who were admitted should be “spread thin” around the country so they would not be seen or heard.

The fact that some of Donald Trump’s predecessors in the White House expressed troubling ideas about blood and genes does not make Trump’s remarks any more palatable. On the contrary, understanding what Warren Harding and Franklin D. Roosevelt said on the subject back in the 1920s or 1930s is a reminder that such ignorant attitudes are part of a bygone era and belong in the dustbin of history.

Thanks to modern science and enlightened perspectives on race and culture, century-old attitudes about one race being better than others generally have been discredited and discarded, except on the fringe—and that’s where they deserve to remain.

(Dr. Medoff is the founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and the author of more than 20 books about Jewish history and the Holocaust. His most recent book, America and the Holocaust: A Documentary History, was published by the Jewish Publication Society of America / University of Nebraska Press. And available on Amazon, as are his other books)Dr. Medoff is the founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and the author of more than 20 books about Jewish history and the Holocaust. His most recent book, America and the Holocaust: A Documentary History, was published by the Jewish Publication Society of America / University of Nebraska Press. And available on Amazon, as are his other books