In 2004, R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr. interviewed Stefan Halper for Tyrrell’s book The Clinton Crack-up. The reason: Halper and Bill Clinton attended Oxford together. They were there at the same time and ran in the same circle with Clinton’s roommate Strobe Talbott. Another, more peripheral member of that circle was a young banker named Edwin David Edwards. He went by David, was an American posted in London, and briefly shared an apartment with Clinton and Talbott. motive for sedition

Clinton went to the U.K. for his Oxford scholarship, and met these various personalities, in 1969. David Edwards continued a lifelong connection with the Clintons, going on to pay for a visit by Bill and Hillary Clinton to Haiti during their honeymoon in 1975, a visit that included a voodoo ritual attended (according to some accounts) by the three of them. (Bill and Hillary Clinton later wrote of multiple voodoo encounters, such as one in which “spirits arrived, seized a woman and a man”; and another in which “a woman, in a frenzy, screamed repeatedly, then grabbed a live chicken and bit its head off.”)

Of more importance to our purpose here, Edwards, who had been with Citibank, moved to Arkansas in the 1970s. There he joined the investment firm Stephens Inc. – the Jackson Stephens company we’ve met before with the connections to the Rose Law Firm and Glenn Simpson’s father-in-law: Jon E.M. Jacoby, the father of Mary Jacoby and a longtime executive at Stephens.

Edwards was an early donor to Bill Clinton’s political campaigns.

The final chapter of particular interest with David Edwards occurred two decades later when he had a four-hour dinner with Bill Clinton in July 1993 the weekend before Vince Foster died of a gunshot wound to the head.

But David Edwards will come up again between his honeymoon gift to the Clintons and his dinner with Bill that fateful weekend.

The action begins

In 1977, Hillary Clinton joined the Rose Law Firm. That year, Stephens Inc. joined forces with Carter administration official Bert Lance, a Georgia banker, in an effort backed financially by the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) to take over the massive U.S. bank-holding company Financial General Bankshares, based in Washington, D.C.

Lance’s part in the attempt was prompted by BCCI’s having bailed out his catastrophically failing bank. He and Stephens obscured the backing of BCCI – a bank founded by Pakistani financier Agha Hassan Abedi and a group of (largely Saudi) Middle Eastern investors in 1972 – but the takeover bid did not win U.S. regulatory approval.

According to the chronology in the Wall Street Journal, “Amid the legal maneuvers surrounding the [bank] takeover attempt, a brief is submitted by the Stephens-controlled bank data processing firm Systematics; two of the lawyers signing the brief are Hillary Rodham and Webster Hubbell.” Regular readers will remember that Mary Jacoby’s father, Jon Jacoby, brought Systematics into the Stephens investment fold and worked the account for many years. (Trump campaign adviser Charles Kubic, a retired Navy admiral, suggested in an editorial in The National Interest in 2016 that the Rose Law Firm’s role in trying to set up the BCCI-backed takeover needed investigation. He was no doubt right about that at the time – but in retrospect, for far more reason than he knew.)

In 1978, Bill Clinton was elected governor of Arkansas. That was also the year the Clintons and another couple, Jim and Susan McDougal, invested in the Whitewater land development tract. McDougal and Clinton had known each other for years, and both of them worked for Arkansas Senator William Fulbright in the 1960s.

Jim McDougal would go on to create the Arkansas-based Madison banking empire, which figured prominently in the Whitewater scandal. In the meantime, Stephens Inc. was working on a relationship formed in the mid-1970s with Indonesian banker Mochtar Riady – the patriarch of the Riady family connected with Charlie Trie (of Chinagate, Clinton-donor fame in the 1990s) and the Lippo Group. In 1976, Stephens and Riady opened Stephens Finance to do business in Asia.

In 1981, a second effort by the BCCI-backed takeover group succeeded in buying Financial General Bankshares. The U.S. bank-holding company’s name was changed in 1982 to First American Bankshares, and Democrat official-about-town Clark Clifford was made chairman.

Patterns intensify

In the interim between the takeover attempts, the Iranian revolution sent the Shah into exile, revolutionary Iran and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq went to war, the global sanctions movement went into high gear against apartheid in South Africa, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, Pakistan and the U.S. began backing the Afghan resistance. An ethics-challenged international commodities trader, Marc Rich, was making big bucks trading with everybody in that mix and many others.

Rich’s specialty: laundering, not just money but the commodities themselves, enabling sanctioned nations and companies to keep selling – and buying – material of real market value, while Rich pocketed a broker’s fee.

Marc Rich, commodities mogul, in later years. Wikipedia

BCCI, the bank with the Middle Eastern investors, was in the same mix. Its game was laundering money. Unlike later examples of money-laundering banks, such as HSBC and BNP-Paribas, BCCI hardly bothered to operate on a solvent basis. It was basically just a giant shell company for moving other people’s money around, which was a key motive for wanting a good foothold in the United States, where there was a whole lot of other people’s money. Naturally, it wasn’t just sanctioned commodities that figured in BCCI clients’ enterprises; it was arms and narcotics too. (See the comprehensive Senate report on BCCI from 1992, linked below.)

One other thing had happened by 1982. Stefan Halper was a campaign official in 1980 for George H.W. Bush and then Ronald Reagan. He had had a fateful, out-of-the-blue discussion with Louisiana and Texas businessman Harvey D. McLean, Jr. about the crazy idea of starting a bank because the world needed just the boutique bank they were thinking of.

Halper was married at the time to the daughter of Ray S. Cline, the CIA’s deputy director for intelligence, and was a veteran of the chief of staff’s office in the Nixon administration, among other early government posts. There’s no need, at this remove in time, to be coy. Those factors, and Halper’s early Reagan administration position as a deputy assistant secretary of State, presumably figured large in his sudden urge to enter banking, for which he had no background.

By 1982, Halper and McLean had their plan drawn up to start a bank in Washington, D.C. In 1983, Halper left the State Department and became president of the Palmer National Bank, headquartered on K Street in D.C., a few blocks north of the White House. The bank was capitalized with a loan from Herman K. Beebe, a notorious figure with known mob connections in Louisiana whose string of questionable, criminal, and failing banking enterprises, many in Texas, crossed paths with a number of our players in the 1980s. Beebe is sometimes called the “godfather of the S&L scandal” of the late 1980s.

(Image: Stefan Halper, Institute of World Politics)

That year, 1983, would be Halper’s last in official government service. From then until the end of the Clinton administration in 2001, he would be a banker, media columnist, academic, and “senior advisor” to the U.S. Departments of Defense and Justice.

The following year, 1984, Stephens Inc. and Riady bought First Arkansas Bankstock Corp. and changed its name to Worthen Bank. Eventually, BCCI principal Abdullah Taha Bakhsh, a Saudi, became one of the chief investors in Worthen. (Stephens, remember, had helped shepherd BCCI into the U.S. as the backer of the Financial General takeover.)

Bill Clinton, still the governor, moved Arkansas state pension funds into Worthen Bank accounts. Unfortunately, the funds quickly lost 15% of their value. Jackson Stephens and Mochtar Riady personally arranged to make up the loss, although I have been unable to track down exactly where Riady got the money from.

By the mid-1980s, meanwhile, the Iran-Contra arms-running scheme managed by Oliver North at the National Security Council was in full swing. Two banks we’ve been tracking were involved in moving money for it: Palmer National Bank and BCCI.

Marc Rich was also a client of BCCI. Rich was no dummy: the notable thing about his transactions with BCCI is that he didn’t deposit money with them; he borrowed it. He could thus use BCCI for laundering funds without having to actually entrust his cash to BCCI’s keeping. In 1983, Rich fled the United States under threat of indictment for tax evasion, moving his home and base of operations to Switzerland. He continued to do business with clients that included Iran, Iraq, South Africa, Libya, other African nations in bad odor with the U.S. and international regulators, and the Soviet Union.

Another client of BCCI was Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega. The BCCI executive assigned to babysit Noriega was a Pakistani in the “you-can’t-make-this-up” category named Amjad Awan. I have been unable to confirm whether Amjad Awan is related to the Awan family with the nefarious I.T. enterprise among Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives, and I do not assert that here.

An unproven (but in-pattern) connection?

It is interesting to note, however, that Amjad Awan tended to Noriega from a BCCI branch in Florida (where Noriega came under indictment for narcotics crime). It was in Florida where U.S. government agents infiltrated the Medellin cartel connection and built a criminal case against BCCI in the late 1980s. Amjad Awan was sentenced in 1992 to 12 years in federal prison for his role in the criminal enterprise.

Manuel Noriega escorted by DEA agents on USAF airlift after his surrender in January 1990. Wikipedia, USAF

Later, in January 2004, Florida Congressman Robert Wexler became the first Democrat to contract for the services of the Awan family, arranging a contract for I.T. support with Imran Awan (then age 23). Later still, after Capitol Police began investigating the Awans in early 2017, Florida Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz went above and beyond in her extremely agitated effort to protect the Awans from scrutiny. She also kept Imran Awan on her House payroll long after a federal case was opened against him, and reportedly was turning a blind eye to his use of her account credentials on the House I.T. network well into 2018.

Regarding the IT Awans (to wrap this segment), I have never been entirely clear on why there is a photo of Imran Awan with Bill Clinton.

Imran Awan with Bill Clinton (Image via Facebook)

The late 1980s: More pattern

Of course, in 1989, when Manuel Noriega was under U.S. indictment for his drug crimes, George H.W. Bush ordered him removed in a military regime-change operation in Panama (Just Cause).

Also in 1989 (as well as the previous year, 1988), the BCCI foundation, ostensibly dedicated to charitable works in Pakistan, made grants of $10 million to the Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology run by A.Q. Khan in Pakistan. A.Q. Khan is the Pakistani who pilfered uranium-enrichment design information from Europe’s uranium consortium, URENCO, in the 1970s, and returned to Pakistan to father the Pakistani nuclear bomb.

The Pakistanis would go on to test five nuclear warheads in May 1998. A.Q. Khan has been implicated in nuclear proliferation to Libya, North Korea, and Iran as well.

A. Q. Khan in his earlier years (he is now 84, in 2020). Via Encyclopedia Britannica

Besides its relationship with Marc Rich and other outside-the-lines traders, BCCI was closely connected with the Pakistani firm Gokal Shipping. Gokal did a great deal of business running cargo sanctioned by the United States to and from Iran in the 1980s.

And we’re not done with the 1980s yet. BCCI and Palmer National Bank aren’t our only links to the Iran-Contra scandal. In 1985, Stephens partners Mochtar and James Riady (James being the son of Mochtar and president of Worthen Bank) arranged to take over the tiny First National Bank of Mena, Arkansas. The main distinction of the town of Mena, population 5,000, is that it became a training site for Contra operatives, and allegedly a hub for activities involving drug cartels and the CIA.

Moving into 1986, the Wall Street Journal chronology summarized some of it thus:

Jan. 17: The U. S. Attorney for the Western District of Arkansas drops a money laundering and narcotics-conspiracy case against Arkansas associates of international drug smuggler Barry Seal. Arkansas State Police Investigator Russell Welch and Internal Revenue Service Investigator Bill Duncan, the lead agents on the case, protest; later, both are driven from their jobs.

Feb. 19: Barry Seal is gunned down by Colombian hitmen in Baton Rouge, La. He becomes the touchstone in murky allegations of covert operations, cocaine trafficking and gun running swirling around his base at Mena airfield in western Arkansas.

Aircraft used in Seal’s operation was reportedly financed by Louisiana mob-cousin Herman K. Beebe, an angel investor in Halper’s Palmer National Bank and slayer extraordinaire of S&Ls across the Southwest.

Marine Lt Col Oliver North appears before the House Foreign Affairs Committee for an Iran-Contra hearing in 1986. C-SPAN video

But wait! There’s more. Worthen Bank, the Stephens Inc. enterprise with Mochtar Riady, shed James Riady as president in 1986. It later attracted investment from Abdullah Taha Bakhsh, the BCCI principal mentioned above.

In 1987, a BCCI affiliate, the Union Bank of Switzerland, bailed out the oil company Harken Energy, which along with many other smaller oil companies, was in a bad way due to plummeting oil prices. (Note that Reagan was winning the Cold War at the time by unleashing the market competition that made this inevitable. Falling oil prices were wreaking havoc with the Soviet Union’s hard-money cash flow.)

Bad bank’s Bakhsh backs Bushes

George W. Bush, then the son of the U.S. vice president, was on the board of Harken. And – more stuff you can’t make up – Harken’s most prominent backer in the years just before the UBS bailout was George Soros. In late 1984, as cited in this report from 2002, “Harken was appointed exclusive agent and manager of Soros Oil Inc., a privately held corporation formed to invest in oil and gas properties. The deal allowed Soros shareholders to exchange their interest for shares of Harken stock.”

The Saudi Bakhsh eventually joined Harken’s board as well. Meanwhile, it was our acquaintance David Edwards of Stephens Inc. – voodoo pal of Bill and Hillary – who arranged the UBS bailout for Harken, in which Bakhsh figured prominently as an investor.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Bakhsh’s U.S. representative, Chicago-based Talat Othman, was attending White House meetings by August of 1990 – when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait – to discuss Middle East policy with the H.W. Bush administration.

Along the way, David Edwards had left Stephens and formed a company with his brother, Mike. The Edwards company, and that of a Houston-based Bakhsh crony and BCCI insider, Michael Ameen, put together a remarkable deal in which Harken Energy was awarded a contract to drill newly discovered oil reserves off Bahrain. This surprised industry observers at the time, given Harken’s small size, complete lack of experience drilling offshore, and precarious financial condition.

Even board member George W. Bush didn’t think it was a good idea. Said WSJ:

“I thought it was a bad idea, ” Gov. Bush said recently [in 1995], because of Harken’s lack of expertise in overseas and offshore drilling. Gov. Bush added that he “had no idea that BCCI figured into” Harken’s financial dealings.

Understandably, many people at the time thought Harken’s amazing run of luck probably had a lot to do with the Stephens-BCCI connection, David Edwards’ brokerage. Considering that he had also just arranged a significant donation from the Saudis to the University of Arkansas – and the fact that the son of the man who had become president, George H.W. Bush, was on Harken’s board.

Presidents Bush, pere et fils. CBS This Morning video, YouTube

Feds slow-roll, stonewall criminal case

A key reason why this part of the story matters is that it was unfolding at the same time U.S. federal officials were trying to make headway with a case against BCCI. At the Department of Justice, for some reason, they were running into a stone wall. Their biggest impediment seems to have been a man named Robert Mueller, then the chief of the DOJ Criminal Division.

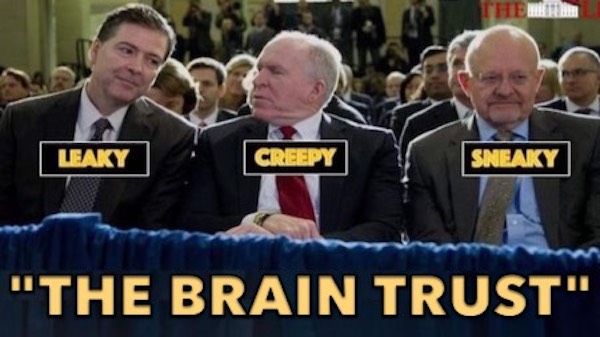

Not only did Mueller appear to slow-roll the federal case against BCCI: he reportedly put out the word that the district attorney offices in New York were not to cooperate with a separate, state investigation being undertaken by Manhattan prosecutor Robert Morgenthau. Others involved in the BCCI case at the federal level included James Comey, then with the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York.

The CIA, likewise, claimed a somewhat astonishing lack of information about BCCI, given the bank’s role in arming Iraq, Iran, the Taliban, and the Contras, among others in the 1980s. This claim was especially incongruous in light of a report prepared by the CIA in 1986, which stated that BCCI was effectively the owner of First American Bankshares – after the Stephens Inc.-brokered takeover in 1982 – but which didn’t make its way to either the Federal Reserve or the U.S. Treasury Department. (The fact that CIA operations were routing money through BCCI presumably had something to do with this reticence.)

A U.S. Senate report in 1992, spearheaded by John Kerry, ended up lamenting the outcome of all this. Although there were some indictments in the U.S., and an investigation in the U.K. ultimately led to a comprehensive takedown of BCCI, the Kerry group’s report contains a long list of things that didn’t get properly investigated when the DOJ had every reason for doing so.

From the Kerry inquiry report to the Senate on BCCI, 1992. (Screencap, author)

Notably, one of those things was the relationship between BCCI and the notorious Marc Rich, still under U.S. indictment and operating out of Switzerland.

Rich spent the 1990s helping the new oligarchs of the former Soviet Union take over the commodities trade and spirit billions in national wealth out of the emerging countries. He profited tremendously off that line of work and pursued it in various venues around Africa too. He was also thought to be involved in the Oil-for-Food profiteering scandal incident to the U.N. sanctions on Iraq, among other sidelines.

Bill Clinton’s big pardon adventure

This little excursion through history winds up, appropriately, on 20 January 2001, the day a departing President Bill Clinton issued a stunning pardon for Marc Rich.

Peter Schweizer, in an article in January 2016, asked one of the right questions about that. The speculation in 2001 centered almost entirely on the point that Rich’s ex-wife, Denise Rich, made large campaign donations to Hillary Clinton (who ran for the U.S. Senate from New York in 2000), and petitioned for clemency on Marc Rich’s behalf in the last months of the Clinton presidency. But Schweizer suggested Bill Clinton wasn’t looking in the rearview mirror when he issued the pardon, or even looking sideways.

Perhaps he was looking to the future. Schweizer points out that the Clintons spent the next 15 years benefiting from the activities of Rich’s network. Nigerian businessman Gilbert Chagoury, for example, who gave at least $1 billion to the Clinton Global initiative and whose family members in the U.S. made significant contributions to Hillary’s campaigns, was a crony of Rich’s. (Marc Rich passed away in 2013.)

Russian investor Sergei Kurzin, who figured prominently in the Uranium One deal brokered by Frank Giustra, worked for Rich in the 1990s.

There were others; Schweizer’s point is an essential one, and he may not have foreseen its full significance when he was writing in January 2016. The point is this: the power to issue permits – and pardons – as a lucrative way of life is one that plenty of people don’t want to give up once they have wielded it. It’s not just a few handfuls of people at a given time who have been presidents or prime ministers. It’s their cabals, their circles of donors and cronies, and revolving-door bureaucrats even at the lower levels who surge in and out of office with them.

This is something more than a “Deep State.”

Over the last 40-odd years, this constituency of regulatory power has been globalized, homogenized, and anonymized to an extent never seen before. Sometimes it can be found making celebrated donations to universities and good causes. Other times it’s covering up the untimely deaths of rogue arms-runners who flew in and out of small towns in Arkansas and Louisiana. Still other times, it’s looking the other way as ill-gotten profits from drug deals and money-laundering get funneled into nuclear weapons proliferation. The right to mine uranium in one country somehow gets awarded to the state-run enterprise of another, increasingly hostile one.

Or … is this constituency really looking the other way on those things? With a deal like Uranium One, is it really all about selling out for the money, for a front-line principal like Bill Clinton, or Hillary?

I am steadily less convinced that that’s what it’s about. These are not stupid people. They know the strategic value – to whoever controls them – of uranium, and oil, and aluminum, and copper and rare earths and other commodities. They understand the dynamic of regulatory power – how it can open a bank’s doors to you, and get the bank to do things you want – at least as well as they understand pocketing a buck.

Moreover, the large circle they run in has a well-defined set of ideological touchstones for these quantities in human life: finance, energy, natural resources, and regulation and organizing for the future. They are not separate from what Soros likes to call the “civil society” of advocates and activists on these matters. They flow back and forth with it.

Everywhere you look, including during the years since Bill Clinton left office, there it is. Unprosecuted skulduggery with one or all of the following lurking in the mix: big banks incorrigibly laundering money and requiring perpetual “monitoring”; ruthless back-alley commodities traders buying grace with payola and endowed chairs at august institutions; shipping operated on a fly-by-night basis through mobile phones with numbers in Dubai that never get answered, and ships registered like name-your-star promotions at a building in the Marshall Islands that looks like an elementary school.

And always, the arms-running, and off in a corner somewhere, someone trying to move components for assembling nuclear weapons around. There’s too much off-hand involvement in it, for this to really be incidental to the money cynical politicians may be making off of using their power to turn a blind eye. No, it starts to look more like it’s the point.

There is one emerging trend we didn’t see nearly as much before the late 1990s. That’s the lost billions and billions of dollars, the dollars that went somewhere, but no one can give us chapter and verse on who got them and how they were spent. Many billions of these dollars belonged to the taxpayers. Some belonged to a public invested unawares in compromised private companies. In either case, we are owed answers that never come. Those dollars went somewhere.

This – this summary of the seamy underside of modern government and its regulatory nexus with business and “civil society” – is what you call motive. Protecting Hillary from prosecution was never worth an all-out seditious attempt to overthrow the presidency duly established by the U.S. 2016 election. Still less was “Obama’s legacy” worth such an effort.

The brain trust, briefing Congress in 2014. (Image: Defense Intelligence Agency)

Sedition is too big a solution for a small problem like Hillary’s fate

For those willing to engage in outright sedition, Hillary, and Obama’s legacy, are expendable. Sedition is too big a solution for such a small problem. But pretty much everything and everyone can be thrown under the bus if the real goal is to preserve a way of life for a regulatory-power class.

YouTube screengrabs

As this shapes up, it looks like the attempt was to hang on to the powers of regulation, resource control, taxation, rent-seeking, defining the purview of government, gaining control of the voting apparatus, and setting limits on the information infrastructure for everyone on the planet. There is also more than a hint that among the powers to be gained is control of a nuclear capability in some form – a capability available apart from the arsenals of sovereign states.

Why was Trump such a threat to this enterprise? I suspect our view into that matter is a surprisingly simple one. Certainly, there is the point that Trump isn’t, and has never been, part of the compromised-government nexus that emerges from this history. But there’s something more.

(Image: Screengrab of White House video, YouTube)

I alluded to it once before in reference to the Jeffrey Epstein saga. Around 10 years ago, Trump, who had entertained Epstein on a few occasions at Mar-a-Lago, was approached by federal officials about some of the allegations made against Epstein. His response seemed to impress them, simply because he expressed his willingness to cooperate and help them in any way he could.

It appears that Trump wasn’t afraid of Epstein’s “black book.” That wasn’t the response the officials were getting from others.

I was reminded of that little episode as I came across another one from many years earlier when Trump was considering opening a casino in Atlantic City. With a somewhat bemused tone, BuzzFeed reported in 2017 that at the time (1981), Trump offered to cooperate fully with the FBI as part of his operating plan for the casino. Again, Trump seemed to simply think of cooperation with law enforcement as a positive and integral aspect of doing business – without bluster or heroic protestations, as if he had nothing to fear.

Trump has plenty of faults, to be sure. But he doesn’t act like someone who’s mobbed-up, compromised, or afraid of anyone’s little black book.

He turned 23 in 1969, essentially the same vintage as Stefan Halper, Bill Clinton, Strobe Talbott, and David Edwards.

But if we have ears to hear, it speaks volumes that Trump wasn’t in the U.K. in 1969 – or, within the next decade, in the halls of government, or catering to them. Their world wasn’t his, and he doesn’t have to preserve it at all costs to have a future.

Cross-posted with Liberty Unyielding

motive for sedition

motive for sedition

motive for sedition

Https://lidblog1.wpenginepowered.com