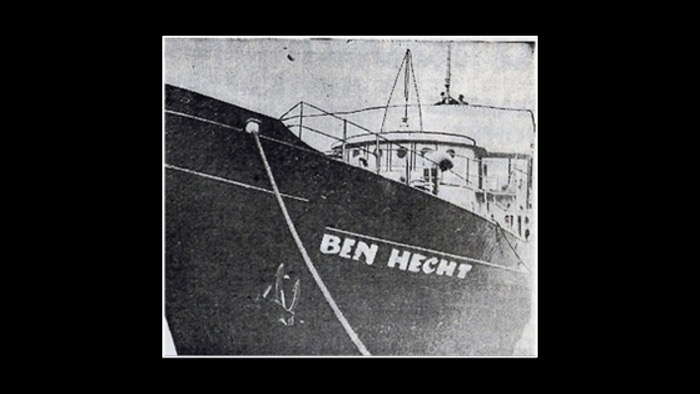

“Irish, sympathetic, hates British, will definitely help.” So read an entry in the diary of Brooklyn housewife Esther Kaplan, after meeting with Rep. John J. Rooney, an Irish-American congressman from New York City, seventy-five years ago this week. The Ben Hecht

Mrs. Kaplan had no background in lobbying or political activism, but when her son David was arrested by the British for trying to smuggle Holocaust survivors into Palestine in 1947, she reinvented herself as a Zionist lobbyist and took her case straight to Capitol Hill.

The arrest of David Kaplan and other crew members of the S.S. Ben Hecht, and the protests that ensued in the United States, comprise a fascinating but little-known chapter in the history of the campaign by Americans to help create the State of Israel.

On a chilly morning in late February 1947, six hundred Holocaust survivors trudged up the gangplank of the S.S. Ben Hecht in the French harbor of Port de Bouc. The ship was sponsored by the activist Bergson Group and named in honor of the journalist and Hollywood screenwriter who authored the group’s most controversial newspaper ads denouncing British rule in Palestine.

The ship’s captain was Robert Levitan, a burly six-foot-four former Merchant Marine who said he “jumped at the chance” to participate in the mission because he had “felt impotent in the 1930s and early 1940s, hearing about Hitler’s persecution of the Jews and not being able to do anything about it.”

“We had twenty men, with twenty different reasons for joining up,” Levitan remembered. “We had some very young boys who were reared in Zionistic homes and were gung-ho Zionists. We had an Irishman who hated the British, and he volunteered just because it was against the British. Our cook was a black man, one of the gentlest men you could ever meet, and he just liked helping out the underdog.”

SALAMI, AND MORE SALAMI

On March 1, the Ben Hecht departed from the French harbor. As the ship traversed the Mediterranean, one of the engines repeatedly broke down, a water tank leaked, and rough weather wreaked havoc. The food supply, however, held steady, thanks to a Bergson supporter in New York who had donated two thousand pounds of kosher salami.

“We had salami soup, salami, and eggs, everything you can think of with salami,” Captain Levitan recalled. Despite the near-starvation, many had only recently endured as prisoners in Nazi concentration camps, “they refused to eat until they confirmed that the salami was kosher.”

“The refugees covered every inch of space,” recalled crew member Robert O’Donnell Nicolai, of Illinois. “Sleeping quarters were any place they could find that was long enough to lie down on … [yet] there was very little complaining. You can’t help admiring people like that. They wanted water, and couldn’t get it; they wanted the sunny side of the deck, couldn’t get that because it was jammed. There were many professional men in the party: doctors, dentists, engineers. In [postwar] Europe all they had to look forward to was digging ditches or building roads. In Palestine, they were going to begin life all over again.”

At first, Nicolai said, “the refugees were inclined to be suspicious of us non-Jews; they couldn’t understand why we had volunteered for the trip. But after they got the idea, which was that we [were] angry at the way the Jews of Europe had been treated, they thawed. From then on, we were buddies.”

On March 8, 1947, just ten miles from the Tel Aviv shore, three British destroyers confronted the Ben Hecht. The flag of Honduras was flying from the ship’s mast, but the British were not fooled by the disguise. “Two of the destroyers slammed into the side of our ship,” Captain Levitan recalled. “You could hear the steel rails crunching and the side of the ship denting.” The crew hastily raised a homemade Zionist flag to replace the Honduran one.

Everyone aboard was arrested. The passengers were taken by the British to a detention camp in Cyprus, where they would remain until the establishment of Israel the following year. The captain and crew, however, as American citizens, were jailed at the Acre Prison fortress, north of Haifa, alongside imprisoned members of Menachem Begin’s underground militia, the Irgun Zvai Leumi.

For some months, the Irgun had been planning an attack on the Acre prison to free its fighters. The plan had stalled because the escapees would need identification papers, with current photographs, to avoid being arrested at British roadblocks. The prisoners had no means of supplying such photos to their comrades on the outside–until Captain Levitan presented them with a small camera that he had managed to bring with him into the prison.

On May 4, an Irgun forces blew a hole in the southern wall of the fortress from the outside, while prisoners used smuggled explosives to destroy cell doors and internal walls. Forty-one Jewish fighters escaped in the daring raid, which the international media described as the most spectacular prison break of modern times—and a major blow to British prestige. The operation was later immortalized in the film “Exodus.”

LOBBYING FOR FREEDOM

Word soon reached Mrs. Esther Kaplan, in Brooklyn, that her son David, the ship’s radio operator, was behind bars. The plight of her son and his comrades transformed the demure housewife into a political dynamo.

“Our home was converted into a beehive of activity,” she wrote. “We borrowed typewriters, and friends came and worked assisting in sending out petitions. Aunt Pearl came, made pots of vegetable soup and sandwiches to feed the helpers.” The newly-enlisted activists wrote letters, organized rallies, and contacted politicians to relate the story of the Ben Hecht.

On March 19, Mrs. Kaplan headed for Washington. With the aid of the Bergson Group and the American Zionist Emergency Council, she met with numerous leading members of Congress or their staff. Some were sympathetic to the Jewish cause because of what the Jews had suffered in the Holocaust; others had their own particular reasons—such as the aforementioned Congressman Rooney, who resented British rule in Ireland and felt a kinship with Jews opposing British rule in Palestine.

Sometimes Mrs. Kaplan’s reputation preceded her; when she met with Rep. Leo Rayfiel (D-NY), she was told that his office had already received petitions bearing hundreds of signatures from Mrs. Kaplan’s supporters back home. Congressman Hugh Scott of Philadelphia delivered a speech on the House floor about the imprisonment of the Ben Hecht crew after hearing from Mrs. Kaplan about her son’s ordeal.

The lobbying had its share of trying moments. Late on Friday afternoon of the first week, Mrs. Kaplan arrived at the home of a local family with whom she would be spending Shabbat. She was emotionally and physically exhausted. Her diary reads:

“Rainstorm, windy, miserable cough and chills … Entered Rabbi’s home late, tired, wet from rain and greatly discouraged. Greeted at door with friendly welcome by [Rebbetzin] Esther Pruzansky and Deborah, 5 years old. ‘Gut Shabbos, please come in and join us.’ What a welcome, warm, genuinely sincere! I could see the candles burning in the dining room, white Shabbos tablecloth gleaming, the challahs covered, the wine decanter … Deborah already made a prayer for me over the candles–a ‘Come Sabbath Queen, bless our guest Mrs. Kaplan’ … I’m crying as I write this …”

Reinvigorated by her Shabbat with the Pruzansky family, Mrs. Kaplan set out for another round of meetings with members of Congress and Truman administration officials.

The lobbying, public protests, and negative publicity took their toll. By the end of March, the British government announced that the Ben Hecht crew members would be deported to the United States.

U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark assured the prisoners that no criminal charges would be brought against them when they returned home. The Truman administration did not want to be seen as persecuting young men who were regarded as heroes by American Jewish voters.

The crew of the Ben Hecht arrived in New York City on April 16, where they were given red carpet treatment at a City Hall reception hosted by Acting Mayor Vincent Impellitteri. Five days later, they were feted at a gala dinner in their honor, hosted by a very proud Ben Hecht, with comedian Milton Berle among its headliners.

Although the ship did not succeed in bringing its passengers to the Holy Land, the voyage of the Ben Hecht generated important international publicity about the plight of the Holocaust survivors in Europe. The unexpected role of the crew members in facilitating the Acre prison break contributed to another blow at the British ruling authorities. And the efforts by grassroots Zionist activists on behalf of the imprisoned crew helped inform the American public about the Palestine crisis.

Mrs. Esther Kaplan never set out to be a lobbyist in Washington. But events thrust that fate upon her, and she rose to the challenge, playing a small but vital part in the historic struggle for Jewish statehood.

(Dr. Medoff is founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of more than 20 books about Jewish history and the Holocaust. This essay is based on his most recent book, The Jews Should Keep Quiet: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and the Holocaust, published by the Jewish Publication Society of America / University of Nebraska Press. And available at Amazon)